NZSA Disclaimer

Good Spirits Limited (NZX: GSH) is soon to be delisted. After 19 years, investors have been close to wiped out as Good Spirits became burdened with debt to the point of effective insolvency. With the final chapter nearly complete, I thought it was worth delving into the past to understand what went wrong and to see if there were any takeaways we can glean from this sad tale.

Good Spirits has been listed under three names in its 19-year history. It IPO’d as Salvus in 2003 before changing its name to Veritas Investments in 2012 and finally adopting its current name, Good Spirits, in 2019.

Chapter 1: Salvus Investments – The LIC

Salvus Investments entered the market as a Listed Investment Company (LIC) with a value-focused manager, mandated to invest in smaller NZ-listed and unlisted companies. Initially, investment performance was reasonable, with Net Tangible Assets (NTA) growing to $1.35 by mid-2007. However, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) struck, causing the NTA to collapse to 80 cents by March 2009. Poor stock selection meant the LIC did not benefit from the post-GFC rally, and by October 2011, the NTA was at 84 cents.

The share price consistently traded below NTA.

The largest shareholder of Salvus was an entity associated with Alan Hubbard of South Canterbury Finance fame, holding a 13% ownership stake in the company. By March 2010, asset liquidation across Alan Hubbard’s assets was in full swing. Bryan Gaynor’s Milford Asset Management acquired Alan’s stake, and Gaynor joined the board as a non-independent director with a 17% stake. Although Bryan was eager to take over the management rights, another value-focused fund manager, Chris Swasbrook of Elevation Capital, advocated for the fund to be wound up, with cash returned to shareholders to restore the share price gap to NTA.

Ultimately, 81 cents in cash was returned to shareholders, and Salvus became a shell company.

While I won’t delve too much into the performance of the investment manager, it’s worth noting that in 2008 they sold the golden goose, Mainfreight, while investing in Pike River Coal!

Takeaway #1: LIC’s discount to NTA problem LICs have pros and cons. While they provide investment managers with permanent capital as fund withdrawals don’t occur, the market prices for shares can trade at a discount to NTA. This can be undesirable for investors who need funds or decide that the manager is not a good allocator, forcing them to sell at a discount, as was the case for much of Salvus’s listed life. Without the action of activist investors like Bryan Gaynor and Chris Swasbrook, these valuation gaps can persist for years.

Although shareholder outcomes were poor, the value destruction to shareholders was nothing compared with what was to come.

Chapter 2: Veritas Investments – The Rollup

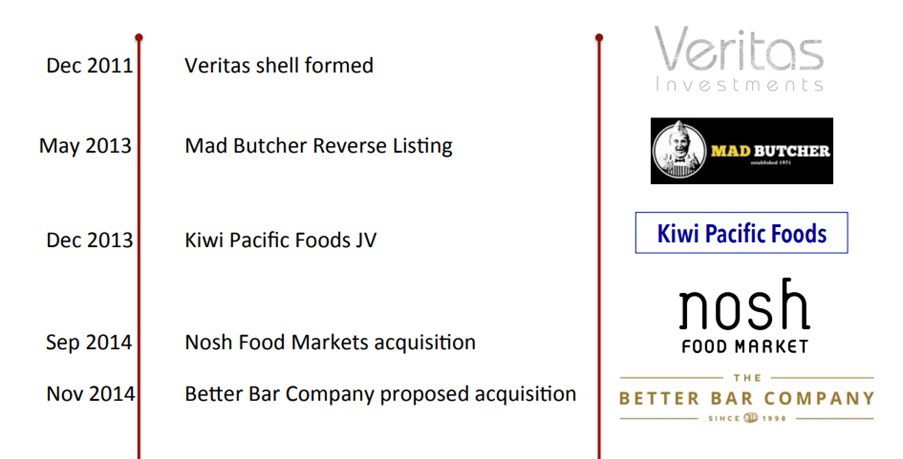

By the end of 2011, the company had a new board led by Mark Darrow and Simon Wallace (Tim Cook was added to the board later) and underwent a name change to Veritas Investments. As a shell, the board was mandated to acquire a company to reverse-list into the shell. This opportunity arose with the announcement to acquire the Mad Butcher in 2012, accompanied by a $25 million over-subscribed capital raise. As shown in Figure 2, three more acquisitions followed in the next 18 months.

Founded by Peter Leitch, The Mad Butcher is a franchisor with 36 franchised locations. Veritas acquired the Mad Butcher business for $40 million from owner Michael Morton. The transaction was paid for with $20m in cash and $20m in Veritas shares. The business was profitable, with more than $4m NPAT for FY14.

Takeaway #2: Reverse Listings Have a Low Success Rate Reverse (or backdoor) listings refer to a process where a privately held company merges with or acquires a publicly traded company that may be inactive or have limited operations. They are sometimes favoured as it means management can avoid the more formal and time-consuming IPO process. However, history tells us this also attracts lower quality businesses with the track record for backdoor listings on the NZX being very poor.

Soon after listing, the business appeared to be struggling. First, the franchises started complaining in the media that the franchisor was taking too much of the profit. Then, stores started to close, with network sales falling from $130m to $80m before it was sold back to Michael Morton for just $8m in 2018.

Takeaway #3: All stakeholders need to do well for a franchise business to succeed For the Mad Butcher, it was clear from the start that shareholder returns were more important than franchisee viability. However, the business was not sustainable without the health of the franchisees. As stores closed, it followed that shareholder returns also suffered. Michael Morton was quoted as saying, “It was a totally different philosophy [as a publicly traded company], with shorter-term goals, especially in terms of profit.“

The next acquisition was a 50% ownership in Kiwi Pacific Foods, a manufacturer and supplier of meat patties. The remaining 50% of Kiwi Pacific Foods is owned by Antares Restaurant Group Limited, which held the Burger King franchise in New Zealand. The purchase price was $2.8m in cash and shares, with the deal consummated in Dec 2013.

This appeared to be tracking along fine with new clients, including Carl’s Jr., but in mid-2015, it was disclosed that “disputes arose between the parties on the interpretation of the supply terms, and Antares sought to terminate the joint venture agreement.” This went to arbitration, and Veritas lost. The joint venture was wound down in 2016, with Veritas writing off $3m.

Takeaway #4: Be wary of customer concentration risk While it was not disclosed what proportion of revenue was attributable to Burger King, it was clearly a high percentage, as the business had no value without that contract. Additionally, businesses with high concentration risk tend to have lower pricing power.

The high-end food grocer Nosh became the third acquisition in September 2014 with a $1.7m price tag and debt-funded $5m working capital injection. Nosh was in a loss-making position and debt-laden (although Veritas did not assume that debt). Michael Morton assumed the CEO position with a view to franchising the existing stores and opening new stores.

However, the business struggled with losses of $1.2m in FY15 and $1.9m in FY16. The emergence of strong competition from Farro Fresh probably did not help. By late 2016, Veritas’s bankers, ANZ, had had enough and forced a sale or wind-down of Nosh. Veritas managed to sell Nosh for $3m, which was used to pay down bank debt.

Takeaway #5: Turnarounds seldom turn Quoting Warren Buffett “Both our operating and investment experience cause us to conclude that turnarounds seldom turn”. Nosh was loss-making and required a business turnaround. The directors had successful business ventures prior to Veritas, so perhaps there was some hubris that made them think they could turn around this business.

Another Buffett quote:

When a manager with a good reputation meets an industry with a bad reputation, it is normally the industry that leaves with its reputation intact.

Warren Buffett

The fourth acquisition was The Better Bar Company (BBC), a group of bars owned by industry veterans including Geoff Tuttle and Peter Sigley for $35m, with $23m paid in cash, $6m assumed debt, and the remainder in scrip. The transaction was funded by a new ANZ debt facility and led to net debt of $33m by the end of 2015.

BBC owned some prominent Auckland bars, including O’Hagans, Danny Doolans and my favourite, The Cavalier. Geoff Tuttle was appointed BBC CEO and later became Group CEO in 2018. The business quickly disappointed with management citing new drink driving regulations causing reduced drinking consumption at bars forcing the board to miss their profit guidance. A more likely scenario is that the founder-led bars are simply run a lot sharper than corporate run bars. The BBC business never did reach the profit expectations promised to shareholders.

Takeaway #6: Rollups need to make sense A roll-up is a term for a corporate strategy of acquiring other operating business to gain scale and efficiencies. Veritas undertook acquisitions where each business had different operating models. Apart from being food and beverage related, the four acquired businesses had few cost or revenue synergies so Veritas failed to get any scale benefits you may look for in a successful rollup. The Board simply tripled the complexity of the group in a short time. In the case of The Mad Butcher and BBC, corporate ownership likely hindered the business rather than helped it.

By 2018, Veritas refinanced its debt (which amounted to $19m after the sale of the Mad Butcher) with a new funder, Pacific Dawn. Veritas paid a bank bill rate plus a 6.5% margin. Additionally, Pacific Dawn received warrants to acquire 19.9% of Veritas for zero consideration. This facility allowed for further bar acquisitions, and in 2019, Citizen Park and Union Post bars were acquired.

Chapter 3: Good Spirits – The Hangover

In 2019, having sold Mad Butcher and Nosh, the company changed its name to Good Spirits to better reflect its sole focus on hospitality. The board saw fresh faces, with the original directors departing, but Geoff Tuttle remained as CEO.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, bringing the ability of Good Spirits to repay its now $27m debt obligations sharply into focus. Clearly, it would have been the wrong time for Pacific Dawn to call in the administrators, so the debt facility was extended, with Pacific Dawn getting another 5% of the company for free.

In November 2021, Good Spirits announced its intention to acquire Nourish Group, an entity associated with Richard Sigley, for $21.3m in cash. The acquisition was planned to be funded through debt and an equity raise. However, by April of the following year, the deal was called off because the Australian equity partners were unable to travel due to lockdowns and the risk of further COVID restrictions.

October 2022 was the beginning of the end. With the pandemic over and conditions improving, Pacific Dawn extended the debt facilities with the following provision:

GSH (and BBC) must achieve certain milestones for a possible range of transactions within a prescribed timeframe. The possible transactions include the subscription for new shares of GSH or its subsidiaries for cash, a merger between GSH and another operator, a sale of GSH’s assets or its subsidiaries’ assets (or a series of sales), or a sale of GSH’s subsidiaries (Transactions).

After a strategic review, it became clear to the board that the only avenue was a sale process.

Takeaway #7: Beware of Leverage Without the global pandemic, Good Spirits might well have been able to meet its debt obligations given BBC was profitable. When unexpected events hit, shareholders effectively lost control of the business to its secured creditors. The previous board’s decision to over-leverage the business with new acquisitions rather than take on new equity and forego dividends heightened the risk profile for the business and was ultimately its downfall.

The independent directors ran a competitive sales process and entered into an agreement to sell to an entity jointed owned by CEO Geoff Tuttle for $20.7 million. Even though further acquisitions had been made, this was well short of the original $35m purchase price back in 2014. It was also well short of the debt owed to Pacific Dawn of $33m. With the business insolvent, GSH will delist with no value left in the business.

Takeaway #8: Vendors know the value of a business better than acquirers Vendors tend to know what a good valuation is to sell their own business. They understand their business intimately, from the cash it generates to the risks and issues it faces. After all, why would a vendor sell unless they are getting a great price? Both vendors, appear to be the only parties here that have not experienced wealth destruction from this saga, having bought their businesses back at significantly lower prices while holding salaried CEO positions in the meantime. Priceless.

While the story has ended poorly for Good Spirits shareholders, my hope is that readers get valuable takeaways from the disaster and be judicious when seeing the inevitable replay sometime in the future.

Chris Steptoe

The author drank the Veritas rollup Kool-Aid for a year or so before realising his folly.

4 Responses

Great article Chris. What a sorry saga this has been. Such a sad fate for some great smaller NZ companies and brands, created by successful entrepreneurs.

Great lessons in this story Chris.

Thank you for the outstanding review of Veritus history. As a holder of Veritus’s shares from an early date I had stuck with my buy and hold strategy as it was not worth selling though mentally wrote off the investment and lost track of all the machinations of the directors.

Great interesting story.