NZSA Disclaimer

FNZ should be a New Zealand success story.

FNZ is a New Zealand-developed business that has gone on to challenge global practices. As FNZ proclaims, its employees have been the key to its success, with the company lauding the involvement of its “extraordinary FNZ’ers” within its ownership structure.

It is that relationship with employees, and their rights as shareholders, which is now coming under scrutiny by the New Zealand legal fraternity and both local and global media.

With the potential for legal challenges from its own employees coupled with challenging financial circumstances created by supercharged growth, the company is now at a critical juncture, at risk of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

Some context

Now a global behemoth, the company was founded as an offshoot of FNZ Capital (later, Jarden) by Adrian Durham to focus on the systems and platforms supporting stock exchanges, fund managers and other financial institutions in undertaking transactions and offering custody management solutions. That has led to a company that operates in over 30 countries, with about 5,500 employees – including 500 in Wellington.

Formally, the company’s head office is still in Wellington – with the company still registered under NZ’s Companies Act, albeit after a brief flirtation with a registration in the tax haven of Jersey. In practice, FNZ’s operational head office is centred in London, led by CEO Blythe Masters.

While a New Zealand company registration offers relatively good transparency, it is notable that the FNZ’s 94.85% shareholder is Falcon NewCo Limited, registered in the Cayman Islands. This is the holding company for at least five major institutional shareholders, including Temasek, an investment arm of the Singapore government, as well as employee-shareholders.

Complexity

There’s no doubt that FNZ operates in a complex landscape – but it seems to make an art form of creating complexity within its own corporate structure. The FNZ Constitution, seemingly prepared by local firm Russell McVeagh, reflects no less than 15 different classes of shares – each with different rights and benefits.

That is also reflected in multiple different classes of directors, on a Board comprising 13 members (with only one of those in New Zealand). Interestingly, the last change was the removal of New Zealand-based Director Charles Trotter, with the Companies Registrar notified of his removal as a director about 3pm today (May 1st), with an effective date of April 1st.

That is the latest in a revolving door of directorship changes over the last few months, with resignations in February 2025 (Richard Wohanka, Mitchell Harris), December 2024 (Benoit Raillard) and October 2024 (Alexander Leitch). Of even more interest are the three updates to FNZ ‘s Constitution within the last 12 months – April 2024, October 2024 and most recently in April 2025.

Those changes are likely to have been at least partly driven by FNZ’s capital raises during 2024 and early 2025 – capital raises that employee shareholders feel have “diluted their shareholder equity by over US$4.5 billion“, according to a press release on April 23rd.

FNZ is not a listed company. That means that individual investors are afforded far less protection than a company listed on any regulated stock exchange (such as the NZX). Nonetheless, there are provisions in the Companies Act that may offer protection and allow remedy for breaches – more on that below.

Financials and Capital Raise

The capital raises undertaken during 2024 are set against a backdrop of a difficult 2023 performance. The most recent financial statements (audited by PwC) are for the y/e December 2023: then-CEO Adrian Durham proclaims a business with $1.4 trillion in funds under administration, 650 partnerships and serving 24 million customers.

He also notes that around half of the company’s 5,500 employees own shares in FNZ.

The company has pursued a strategy of continued expansion to extend geographic footprint, with a strong focus on growth by acquisition. In FY23, FNZ purchased four companies, with FNZ equity used as part consideration in two instances. FNZ reported US$1.5b revenue, but also a bottom-line net loss of -US$550m (an increase from FY22’s loss of -US$318m). On a positive note, operating cashflow is strong at over US$500m.

While amortisation of all those acquisitions contributes, much of the loss appears to be created by a mismatch of ‘business as usual’ costs with revenues.

In FY23, the Group noted that it had received related-party loans from existing shareholders.

Global behemoth or not, total equity stood at only US$689m out of US$6.3 billion of total assets as at December 2023. That, perhaps, sets the backdrop for the capital raises and debt restructuring that were to follow during 2024 and early 2025.

During August 2024, the company announced that it had raised US$1 billion in new equity from existing institutional investors. That was followed by a US$2.1 billion debt refinancing in November 2024. Employee shareholders have reported yet another share issue on April 5th 2025 for a further US$500m.

Legal challenge

It would appear that those employee shareholders have finally had enough. That’s the same constituency and their alignment highlighted by both Adrian Durham and FNZ Chair Gregor Stewart as being a critical priority for the company. Those employee shareholders are reportedly considering an application to the New Zealand High Court. While lawyers, Meredith Connell, will determine the means, this is most likely to be under s.174 of the Companies Act, on the basis that the actions and conduct of the company and its directors have been “oppressive, unfairly discriminatory, or unfairly prejudicial” to their interests.

Conveniently, s.175 offers a list of “certain conduct deemed prejudicial“, which includes references to s.45 (pre-emptive rights) and s.47 (consideration).

Like many companies, FNZ has “contracted out” of s.45, including section 3 in its own Constitution. Notably, this was one of the sections that changed in the October constitutional amendment highlighted earlier in this commentary, following the capital raise announced in August. It appears to offer anti-dilution protection ONLY to those holding voting shares, applicable to the aggregate of all shares they hold (regardless of class). More on that below.

s.47 of the Companies Act requires (in various sub-sections) directors to sign a certificate “stating that, in their opinion, the consideration for and terms of issue are fair and reasonable to the company and to all existing shareholders“.

Director certificates have been filed for issuances in April 2025 and September 2024. While the Directors attest to the consideration and terms being reasonable to the company and its shareholders, it is easy to understand why employee-shareholders are likely to request further transparency as to exactly how FNZ directors came to this judgement.

The Companies Act also clearly sets out the “Director Duties”, that are well-known to most New Zealand-based Directors. Of interest, s.134 states that “A director of a company must not act, or agree to the company acting, in a manner that contravenes this Act or the constitution of the company.”

We can only speculate as to the exact nature of any litigation or application that will be made by FNZ’s employee shareholders. But these elements of legislation (and others) at least raise the spectre of potential legal action – particularly for a company as large and potentially valuable as FNZ.

The company has now taken steps to offer its employee shareholders “catch-up” shares, with consideration for any issuance payable within 15 days (according to provisions in the FNZ Constitution). Whether this will avert legal action is yet to be seen.

Employee Shares and Ownership

So just how much of FNZ do employees own? The existence of 15 different classes of shares, each with different rights and terms, make this difficult to calculate.

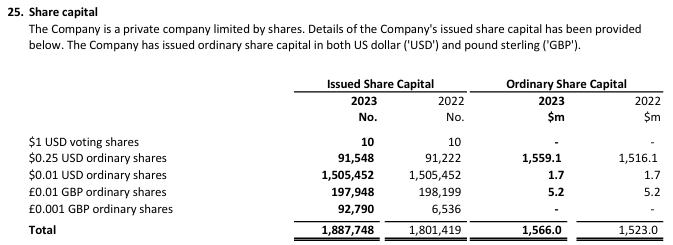

As at December 2023, FNZ’s ‘Note 25’ within its financial statements expressed its share capital in different denominations of “repayment” (par) values in USD and GBP – a well-outdated concept in NZ, but one still used in the UK and US. The relationship of share classes to “repayment value” is described in the company’s constitution.

But here’s the kicker. The only shareholders able to vote at company meetings are the holders of the (10) voting shares described in the table above – albeit they have no rights in terms of distributions / dividends, nor do they participate in any winding-up event.

That means the controlling interest in FNZ is determined by very few shareholders. Those same shareholders economic interest is likely determined by the other classes of shares they hold (‘A’, ‘C’ and ‘D’), represented by the US$0.25 repayment value shares shown above. As the table shows, this represents the lion’s share of contributed capital in the company accounts.

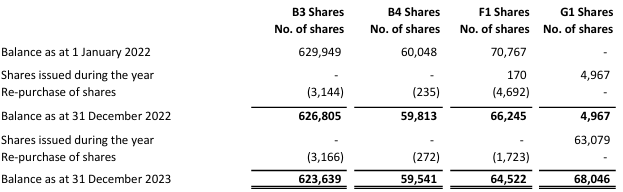

At the end of 2023, employees own at least 5 different classes of shares: B3, B4, F1, G1 and G2. These equate to the shares shown as US$0.01 repayment value (‘B’ shares), £0.01 (‘F’ shares) and £0.001 (‘G’ shares) in the table above. Employees appear to own no Class A, C or D shares (‘Ordinary’) shares that comprise the 91k USD$0.25 shares shown in the above table, nor any of the USD$1.00 ‘voting’ shares.

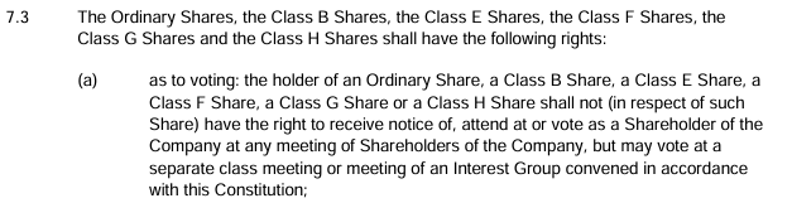

Therefore, the classes of shares owned by employees carry no voting rights at all for FNZ, a factor that allows them no direct voice or representation on the company’s Board but also is likely to affect their ultimate economic value also. Clause 7.3 of the company’s constitution sets out the voting rights of these shares in clear terms.

While the economic rights are set out in…well, less clear terms, they appear to be (in general) subjugated to the rights attached to other classes (A, C and D). Frankly, this is difficult to determine from the convoluted expression of priorities across the 15 different classes of shares.

So just how much of FNZ do employees own? Their press release states 35%, but on the basis of public disclosures, it seems to be a relatively difficult exercise to determine economic ownership, given the lack of market liquidity, the complexity of the share structure and the rights attached to employee shares relative to other classes of shares.

What can be calculated is that as at December 2023, employees owned around 45% of the US$0.01 shares and £0.01 shares on issue, with Employee G1 shares representing 73% of the £0.001 shares on issue. How much this translates to in terms of economic value is indeterminate from public disclosures, with the ownership meaning nothing when it comes to control.

In this context, the employee shareholders are truly reliant on any protections that may be offered to them through the New Zealand Companies Act.

Key Messages

NZ Shareholders Association is generally supportive of employee share ownership schemes operating in listed companies. While dilutive to external shareholders, they build alignment and encourage productivity through employees having “skin in the game”. We’re also aware of a number of employee share schemes operating in the ‘unlisted’ space.

For employees, however, the saga at FNZ sheets home a number of considerations employees should consider. First, their rights as a shareholder are very different to their rights as an employee. It is truly important to understand the rights and obligations associated with employee shares, as a means of determining their actual value.

Shares offered to employees within an ‘unlisted’ company essentially treat employees in a similar manner to wholesale investors – with the expected level of investor sophistication required. It does not necessarily follow that employees of FNZ (a financial services systems provider) are well-tuned to all matters investment, simply by virtue of the industry that are their customers. This is even before an FNZ employee has to understand the impact of 15 different share classes.

That doesn’t mean that unlisted companies should not consider share schemes as a form of reward. But it does encourage clear, simple disclosure for employees so that they are clear as to exactly what they are receiving, the risks they will face and their own rights as shareholders.

Second, liquidity matters. Shares issued within a listed company environment are easily tradeable by employees for a recognised market value. Shares in an unlisted company are not.

Third, Independent Directors matter. This is a key difference between unlisted and listed markets in New Zealand; the Companies Act offers no concept of independence, with the factors that govern independence contained within the Listing Rules of each exchange. The NZX requires companies to consider a non-exhaustive set of factors when Boards are assessing independence – ultimately, that is a form of protection for individual shareholders. NZ Shareholders’ Association has been a core proponent of independence for this reason.

Would FNZ employee shareholders have benefitted from having independent directors on the FNZ Board? Given the lack of voting rights, it may be arguable – but at the very least, independent directors are more likely to have brought a different perspective to the FNZ Boardroom.

For individual investors in listed NZ companies, it highlights once again why NZSA encourages investors to consider whether they are truly aligned with the interests of any dominant shareholder or shareholder group.

A couple of years ago, the NZX offered a short consultation as to whether our listing rules should allow for the introduction of ‘dual class’ share structures, similar to commonly-held US stocks.

NZ Shareholders’ Association offered some short, sharp, clear feedback on that occasion. The situation at FNZ has done nothing to change our mind.

Oliver Mander