NZSA Disclaimer

This is Part 1 of a two part story, focused on the potential for a step-change in KiwiSaver following the Government announcement on November 23rd. This commentary focuses on some of the key questions and trade-offs that could be raised as the proposal is tested in the 2026 election. Part 2 (in the next edition of Informed Investor) will focus on how we use our accumulated savings in the “retirement of the future”

KiwiSaver has been a feature of our investment landscape since 2007. I’ve written about its growth in a previous edition of Informed Investor, observing the increase in KiwiSaver from a standing start to approximately NZ$130 billion at the end of June 2025. That pales in comparison to the AU$4.2 trillion invested in Australian pension funds – a function of an earlier start point and higher contribution rates.

The announcement by Prime Minister Luxon on November 23rd to create a 12% KiwiSaver contribution has been a long time coming, encouraged by the managed funds sector and investors alike. The proposal, such as it is at this early stage, is a ‘halfway house’ towards New Zealand’s slow but inevitable move to create a superannuation structure that can be sustained in the long term. It envisages a 6% contribution rate from both employer and employee – a significant difference in structure to the Australian equivalent where the 12% contribution rate is borne solely by the employer.

Leadership is not always about doing what the people want. More often than not, its about doing the right thing – often in the face of adversity. The integrity behind political will oft givers way to the power of popular consensus. Given the nature of short-term democracy, it can be difficult for politicians to take the tough decisions. In that context, political consensus between major political parties is critical. When it comes to nurturing KiwiSaver as it heads into its youthful 20’s, let’s hope we get that consensus – because in the long-term, this is too important for our country to ignore.

Some jargon and a bit of maths

Consensus or not, there’s no doubt that superannuation will become a key issue heading into New Zealand’s 2026 parliamentary elections. So, let’s prepare you for the sort of jargon that you might hear on the campaign trail…

SayGo vs PayGo

Nope, this is not a description of a type of starch extracted from the inner trunk of the Sago palm. SayGo is industry shorthand for a “save as you go” superannuation scheme. KiwiSaver is a good example of this, with contributions from employers and employees adding up to create savings for retirement throughout an employee’s lifetime.

PayGo is the exact opposite, a scheme that pays out money as it is needed to beneficiaries – or “pay as you go”. Our universal NZ Super is an example of this.

There are some pros and cons to both – but for New Zealand, the rapidly increasing proportion of over-65’s becoming eligible for NZ Super in the next 30 years, funded by an increasingly proportionately smaller workforce should be a strong lesson in one of the key disadvantages of a PayGo structure. Over 65’s will increase from 16.5% of New Zealand’s population to 23.3% by 2050.

KiwiSaver’s SayGo approach has seen an increase in savings rates in New Zealand over the last 20 years, but that does mean that cash is unavailable for spending in the wider economy in the short-term, either to support living costs or in support of other productive investments (eg, capital investment in a business).

The NZ Superannuation Fund (NZSF) has approximately $85 billion invested (as of June 2025) on behalf of New Zealanders. Given its purpose, this is another form of SayGo scheme, benefitting all Kiwis in the long-term.

What this tells us is that current superannuation structures in New Zealand are relatively well-diversified in terms of their design – perhaps unsurprising given that New Zealand began its transition from PayGo to SayGo back in 2007.

A bit of maths

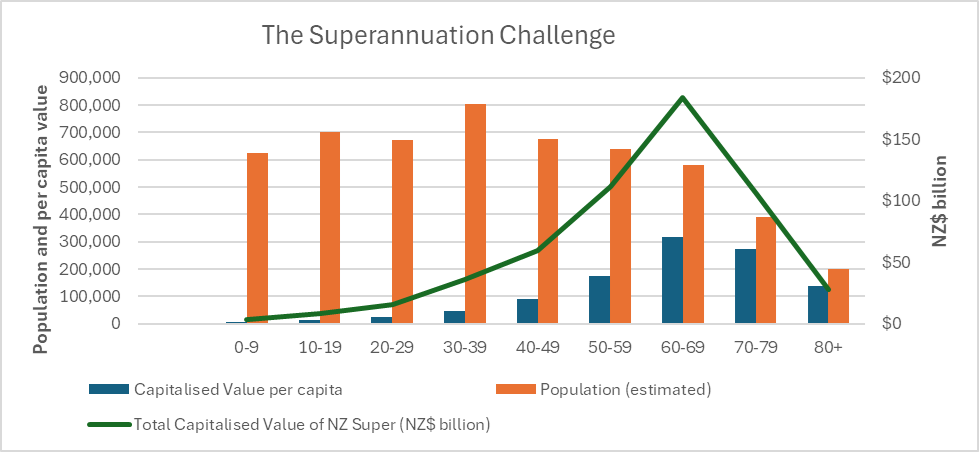

If we assume the average rate for NZ Super (pre-tax) is paid at $29,000 per annum, taking into account the differential rates paid to couples and individuals, and is paid for an average of 25 years, that translates to a capital value of about $343,000 at 7%. Put another way, were you able to sell your entitlement to NZ Super (remember – you can’t), that’s the approximate sum you might be willing to accept at age 65, assuming you live to age 90.

Either side of 65, the capital equivalent value decreases – due to reduced annual payments for the over 65’s or the magic of compounding for those with time on their side.

The total value of the government “buying out” all current and future NZ Super entitlements (at 2025 values) is an eye-watering $553 billion.

Of course, the NZ Government does not have to buy its way out of the financial commitment associated with NZ Super. And at an estimated cost of $553 billion, why would it? Were affordability to be challenged, it is much easier to just change the rules – perhaps through a gradual increase in the age of entitlement, or reducing entitlement for younger generations.

This (admittedly simplistic) analysis shows us three key things:

- First, the criticality of NZ Super increases once a beneficiary turns 50, with the equivalent capital value increasing rapidly each year.

- Second, while the capitalised value of $553 billion is unaffordable and clearly out of reach, that is perhaps an indicator of just how difficult it could be to maintain NZ Super at current levels and entitlement.

- Last, the role of the NZ Super Fund (currently $85 billion) in either funding ongoing NZ Super payments or “bridging” NZ to a savings future.

The analysis is simplistic, in the sense that it takes no account of tax. So, now it’s time for a bit more jargon…

E and T

There’s 26 letters in the English language alphabet. When it comes to the powers that be in designing retirement savings schemes, ‘E’ and ‘T’ are two of the key ones. No, I don’t mean a certain 1980’s movie…they simply stand for ‘Exempt’ and ‘Taxed’.

Simplistically, there are three key components that determine the amount of cash available to you in your golden years. The first are contributions – the amount of money that you (or your employer) contribute to your retirement savings. Next come the earnings, which are simply the returns earned by your savings. Last, there comes a time in your life when withdrawals become important.

Different countries apply different tax treatments to these three key components. For example, in New Zealand, contributions to KiwiSaver are taxed, as are the earnings of your chosen fund. However, any withdrawals are exempt, as tax has already been paid earlier in the life cycle. That makes KiwiSaver a TTE regime (similar to Australia), with withdrawals exempt from tax.

That makes us comparative outliers compared to the UK and the US, where both contributions and fund earnings remain untaxed, while withdrawals are taxed.

As always, there are advantages and disadvantages attached to different systems. Broadly, an EET regime encourages high rates of personal saving, particularly among high income earners – although the Government does not receive tax revenue for decades. On the other hand, a TTE regime (like KiwiSaver) is simpler to operate and fairer from a tax equity perspective – but does less to encourage greater saving.

The next generation of KiwiSaver

There are probably things that we can do to encourage greater savings, thereby overcoming the most significant disadvantage of our ‘TTE’ KiwiSaver regime. The below is a list of random ideas, some supported at different times by New Zealand’s best brains – including, at one time, Prime Minister Luxon in his former membership of the Prime Minister’s Business Advisory Council advising former PM Dame Jacinda Ardern.

“Kickstart” payments for children at birth

Most individuals do not start contributing meaningfully to KiwiSaver until their first job, often in their late teens or early 20’s. A one-off payment at birth means that children will generate earnings that are likely to make a material difference as they transition to adults.

Higher Contribution Rates

An increased contribution to KiwiSaver is not necessarily an argument against NZ Super – but it will certainly offer more financial resilience to New Zealanders in their retirement.

Limit on first house withdrawal

The risks associated with an overheated housing market should be well known to most New Zealanders. And yet, we love our houses…

However, increasing KiwiSaver funds should not be used to encourage higher market pricing for first home buyers, fuelled by withdrawn KiwiSaver money.

Compulsion

At a national level, making KiwiSaver compulsory is likely the least contentious measure available to the Government to improve national savings rates. Of KiwiSaver’s 3.3 million members, 1.25 million (38%) are not currently contributing. The major reason cited is an inability to afford contributions, although there are a variety of other factors impacting contribution rates. If affordability is a major factor, there are several potential government-supported solutions to overcome this; while this might feel like welfare, there is likely to be a trade-off between supporting savings earlier in life to avoid larger payments later.

KiwiSaver looms large in our consciousness, but we are still not at the point where every member thinks of themselves as an “investor” or “shareholder” in businesses. KiwiSaver will help New Zealanders develop individual financial resilience, rather than being solely dependent on future government policy relating to NZ Super decisions.

As KiwiSaver continues to develop, it is this cultural development that will make the greatest difference to Kiwis retirement planning, investment literacy and “commercial knowledge” – with an increase in capital and labour productivity a likely outcome.

The proposals made on November 23rd to make a step change in NZ’s KiwiSaver contribution rates are a great start.

In Part two:

The power of ‘de-cumulation’

The importance of saving for retirement has been drummed into us for decades. But with KiwiSaver now approaching adulthood, with consensus political support emerging that support its expansion, what does that mean for how we think about spending in retirement?

Oliver Mander